This page is a little more personal, initially including some of the reflections, thoughts and ruminations of an ageing business scholar, Peter John Sandiford. We would welcome other contributors to this section – simply follow the instructions in the guide for contributors (linked above) to submit your reflective accounts, reviews and insights. Please mark such submissions as “grumpy poet blogs”

*****

PAGE CONTENTS

- Using Film as an Ethnographic Starting Point, Guest blog by Dr Sandra MacDonald; June 2025

- The Ubiquitous Sonnet; May 2025

- Thoughts on the Hauntingly Hospitable Cherry Tree Inn: April 2005

- Playing with music in business scholarship: February 2025

*****

Using Film as an Ethnographic Starting Point, Guest blog by Dr Sandra MacDonald; June 2025

Sandra MacDonald, June 2025

I am writing this as a reflection on some work I have been doing about my home town of Nairn in the North East of Scotland, near Inverness and on the coast, overlooking the Moray Firth. To give some background to this here are some brief facts about the town.

The town is known for tourism, formerly for fishing (now long gone) and farming in the rich lands that run down to the coast from the Cairngorms. It is a small town with a population of 10,000 people and was formerly a Burgh in its own right, a Burgh in Scotland being an autonomous administrative region. This type of local administrative unit was established in the 12th C. by King David of Scotland.

The use of visual methods in research (I am not limiting this to business/organisations) has always interested me and I have used photographs myself in a fairly limited way. The literature on visual methods covers a wide range of uses, for example as a prompt, as a way of reaching groups who have limited language (children for example, see Brown et al, 2020). The use of images of participants is of course problematic, particularly now that research practice is (rightly) more heavily scrutinized and concerns about using images of people are given serious attention.

The work I am doing started during Covid19 when I was looking at library resources from the National Library of Scotland and came across their Moving Image Archive where I found a number of unedited 16mm films made by amateur filmmakers about the town in the 1950s and one short film from 1934. I was completely entranced by this view of my hometown in an earlier time and wanted to share it so I set about making an edited compilation film to show to anyone who was interested locally. There were several films of varying quality and the compilation had to be short in order to meet the requirements for a distribution licence so I got this edited down to twenty-five minutes and also digitized so I could show it. Luckily I found an outlet for it at the annual Nairn Book & Arts Festival. Showing the film gave me immense pride but also a real desire to use this piece of work in other ways. It has been shown again at the Community Cinema and because of that the local University of the Third Age History Group asked for a showing. This is not a straightforward procedure because each showing has to be licensed by The Moving Image Archive and there are third party copyrights involved.

Writing about visual methods in social science research Spencer (2010) quote from Geertz (1973;10) who likens doing ethnography to “trying to read….a manuscript.” I think this is what I was trying to do and in trying to give context to the film (text) I started to pursue many “clues” as I saw them, to the “manuscript” of the film(s).

The work I am doing started during Covid19 when I was looking at library resources from the National Library of Scotland and came across their Moving Image Archive where I found a number of unedited 16mm films made by amateur filmmakers about the town in the 1950s and one short film from 1934. I was completely entranced by this view of my hometown in an earlier time and wanted to share it so I set about making an edited compilation film to show to anyone who was interested locally. There were several films of varying quality and the compilation had to be short in order to meet the requirements for a distribution licence so I got this edited down to twenty-five minutes and also digitized so I could show it. Luckily I found an outlet for it at the annual Nairn Book & Arts Festival. Showing the film gave me immense pride but also a real desire to use this piece of work in other ways. It has been shown again at the Community Cinema and because of that the local University of the Third Age History Group asked for a showing. This is not a straightforward procedure because each showing has to be licensed by The Moving Image Archive and there are third party copyrights involved.

In order to give context to the next showing and since the audience are interested in history I began to go through local newspapers for years that are covered by the film. Individual moments from the film also led me to pursue specific paths and to keep following the trail to make sense of things that at first seemed puzzling. This has been richly rewarding and provided links to events that were local and national and even global. I feel as if I am doing research in reverse and at the most basic level using a visual prompt to derive research questions rather than starting with a question and using visual methods to help answer the research questions.

Looking at the literature on visual research methods I can’t find anything that speaks about what I am doing. Maybe that is because it is not a good idea! It has launched me into a much more detailed look at various aspects of life in the period (roughly 1953-1960) and documents the changes that are underway and the post-war challenges that people faced. I have been delving into other archival sources beyond the local papers to expand what I know about various aspects of life and work in the town.

You might think that anyone could have done that in a more conventional way but to me the visual clues and prompts are what are directing this study of what some might classify as a “peripheral” region. As with all attempts at ethnography there is a certain amount of chaos in what I am seeing at the moment but I am persevering. It is also my own story as I was a child at the time that the film portrays and recognize place and events and even people sometimes. One other thing I still have to do with the film is show it to Care Home residents and hopefully get to hear (and possibly record) their memories of those times.

I have written organizational ethnographies and used pictures but the moving image seems much more powerful and evocative, probably because it is also personal in this case but I am not sure about that. However, that doesn’t mean there is no value in doing it and although I don’t know what eventually will evolve from this I do know that I have enough historical context, promoted by the images, to give the U3A some feedback. I think there are multiple stories here, not least one about methodology. I hope you find this of some interest and it would be really helpful to hear what you think about my film making journey.

References

Brown, A., Spencer, R., McIsaac, J.-L., & Howard, V. (2020). Drawing Out Their Stories: A Scoping Review of Participatory Visual Research Methods With Newcomer Children. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920933394 (Original work published 2020).

Geertz, C., (2017) The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books.

Spencer, S. (2010). Visual research methods in the social sciences: Awakening visions. Routledge.

Submitted by Dr Sandra MacDonald, 01-06-2025

*****

The Ubiquitous Sonnet; May 2025

Peter John Sandiford, May 2025

I’ve often found that writing a bit of poetry can help address writer’s block, while it can also help rethink a problem. After all, starting a poem is one of the easiest things in the world to do, though finishing one is another matter. I’ve developed a fondness for sonnets, in particular. This is probably “slightly” annoying to colleagues and students alike. For more than a few years my go-to suggestion for researchers who ask how to start writing (proposals, articles, theses etc) normally raises eyebrows and fuels sighs: “You could always write a sonnet about it.”

I believe literary thinking can apply to other areas of scholarship – yes, even social/business research. The old idea that novelists are failed short-story writers and short-story writers are failed poets keeps me going nicely. If so, is the research monograph for less-skilled article authors while the journal article is trumped by the shorter chapter, abstract or summary? Of course there are plenty of examples of great books, unreadably dense journal articles and meaninglessly superficial abstracts. There will always be poor writers, especially in those academic disciplines that value communicative clumsiness. Formulaic, jargon ridden and abusive to the English language (and others too, I assume), academic writing often seems constructed to obfuscate, or at best, exclude from our ideas those who can’t (or can’t be bothered to) decipher disciplinary prose.

In an era when rhyme is rather passé and free verse is the In Thing, I probably seem a little old fashioned. However, I think both have their place in literature

(I also enjoy reading and writing stream-of-consciousness,

evocative, visually suggestive 😉

or

chatty free verse

with or Without

Capitals).

I find that sonnets’ more formal rules force a sort of creativity that free verse, a short story, novel, 2,000-word conference paper, 10,000-word article, 100,000-word thesis, 250,000-word monograph or 14 volume epic saga (sorry Robert Jordan) cannot hope to. Elegance, metre and rhyme also add much to any writing. They offer readability while leaving the reader room for their own interpretation and insight. I suppose, this is why I’m also drawn to the Three-Minute Thesis.

For me, poetic readability extends to reading aloud – surely reciting and listening to tight verse offers a sort of literary exposure that we rarely experience in academic writing; the closest we come to it is the conference presentation, where poor, unprepared, rushed and powerpoint-heavy speeches tend towards monotone script reading, with excessive ‘um’, ‘like’, ‘you know’ and similarly irritating fillers littering performances. Don’t get me wrong, there is little more effective than a skilled public speaker introducing their latest research and/or ideas; it’s just that this seems rarer than ever (and I know I’m as guilty as anyone in this). I’ve recently presented two conference papers wholly or partly in verse – not sure how the audience felt about this, but it was challenging and fun for me.

I’m not sure if it is true (is anything?), but I like to tell myself that nothing that can’t be said in a sonnet is really worth saying. OK, I realise longer forms of writing can explore an idea in greater depth and across different perspectives, but insightful and/or provocative messages can be shared with an audience very effectively in short-form verse. This could suggest that the Haiku is close to the ultimate form of expression on paper.

Returning briefly to the sonnet; they are often seen as verses of love and passion, usually with a twist at the end. However, greater writers than me have used them in different contexts. Most recently I have enjoyed some of Oscar Wilde’s sonnets offering some of his best satires on empire and 18th century politics (I’d suggest Theoretikos or Sonnet to Liberty, Wilde, 1994, p.8 and p.1 respectively).

Reference:

Wilde, O. (1994) The Works of Oscar Wilde, Ware, Herts: the Wordsworth Poetry Library.

*****

Thoughts on the Hauntingly Hospitable Cherry Tree Inn: April 2005

Peter John Sandiford, April 2025

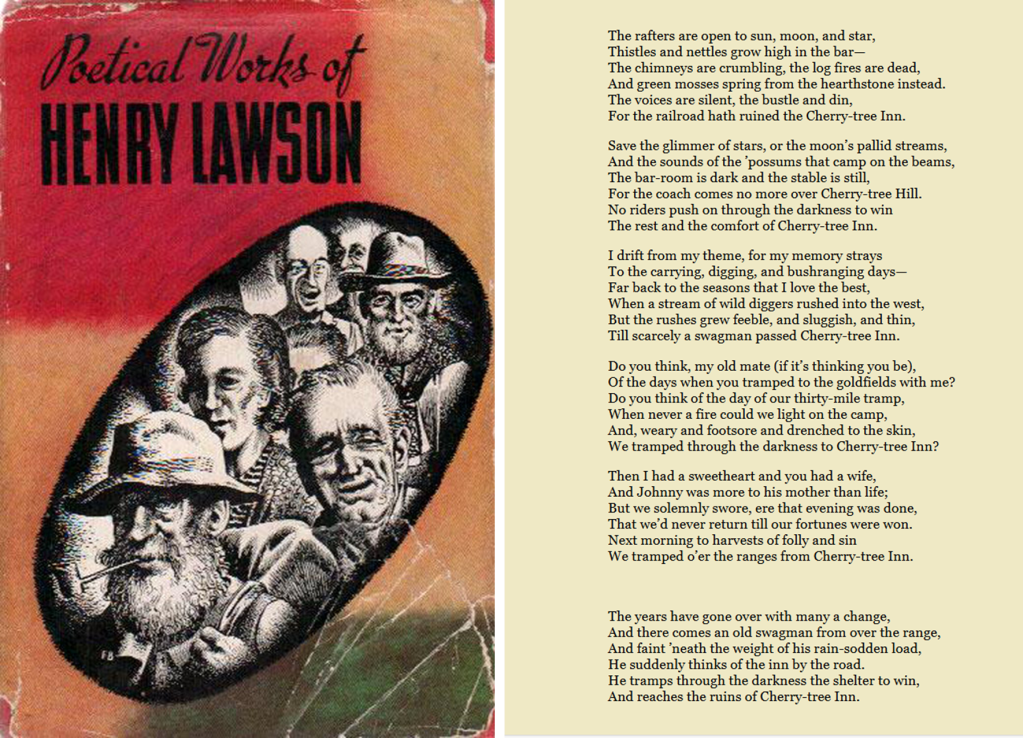

Images from Lawson, H. (1925; posted 2020) Poetical Works of Henry Lawson, Angus and Robertson * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 2001251h.html. Accessed 5-04-2025 from https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks20/2001251h.html#CherryTreeInn

Henry Lawson’s poem the Cherry Tree Inn Lawson, (Lawson, 2020) is seen by many as a rather downbeat and pessimistic piece of nostalgia. The Inn is presented as being ruined by the coming of the railroad, in a similar way to the railways being ruined by private cars in areas where branch-lines disappear, leaving station houses to fall into disrepair unless otherwise repurposed. My childhood’s home village’s (Walsingham, in the UK) railway station is now a Russian Orthodox chapel and I’ve seen others becoming shops or museums.

Lawson begins with plenty of powerful imagery of decay when describing the ruined Inn. He contrasts this with the past, seen through the sort of rosy glasses that humans often use. In sociological terms we might look at this as akin to community lost, an idea that has influenced my thinking for quite a long time (my article with Peter Divers in 2011 illustrates this, discussing the discourse of social decay used to illustrate the loss of community pubs in the UK).

Despite Lawson’s nostalgic yearning, he goes beyond seeing this as a simple past truth – hinting at greater awareness throughout the poem. The highpoint is probably when the narrator (unlikely to be Lawson himself) and his three mates find succour in the Inn after a tiring and uncomfortable thirty-mile tramp one day (and night) in the rain and being unable to even light a fire on the camp. Although he loves these long ago seasons the best, they don’t sound particularly pleasant all the time. Perhaps his nostalgia is more for a sort of innocence, shared with his single-minded mates, being unaware of (or ignoring) the inevitable harvest of folly and sin; perhaps he feels he should have known better, but he certainly does not sound particularly regretful, save for their loss.

This poem is full of ideas of hospitality, without actually sharing any specific images within the Inn in its heyday, except for general ideas of rest, comfort and shelter and the pact the three mates made in the evening of the thirty-mile tramp. Lawson’s memory strays to the bigger picture of youthful impetuosity, but keeps returning to the Inn. I wonder if this is where nostalgia for partial memories (after all, none of us remembers anything objectively) raises a question in our own minds when we read about past society and hospitality, using idealised glimpses of the past as a way of identifying the perceived and actual flaws of the present.

The last stanza sparked my strongest reaction. An old swagman (could this be the narrator or one of his mates, still unsettled in the harvest of their earlier behaviour and far from sweetheart, wife or mother?) struggles through the rainy night as the three had done together, only to be shattered by the discovery that the Inn is in ruins with no warm welcoming glow of fireplace or conviviality. Or does the memory of warm hospitality keep him going through the rain and dark? Does the, albeit broken down, building still have a vestige of shelter to offer, keeping out the worst of the weather? Could a fire be more easily started among the green mosses covering the hearthstone than on bleak, exposed scrubland?

Nostalgia is often seen as problematic; in the past it has been interpreted as a sort of disease. But here, it clearly helps the old swagman keep going despite his heavy load and the soaking rain. So, he only reaches a ruin, but in my most optimistic frame of mind, I would see even a stone ruin as preferable to an outback scene where the sparse native vegetation has been stripped bare by commercial over-grazing and feral camels, rabbits or goats. The Inn still offers hope and limited shelter. Is the memory of hospitality experienced before and revisited mentally and emotionally, sufficient impetus for his potentially life-preserving behaviour? Are we hospitable (rather than hostile) to others because of how we remember being greeted generously before? Is the ethos of hospitality more important than commercial reward? And, perhaps most importantly, is the mental warmth of a memory crucial to our humanity towards others? As a final taste of situational irony, this desolate and dilapidated Inn could offer more authentic hospitality than an over-priced city-centre “pub” with access policed by disapproving glances from uppity service staff and clientele, cover charges or over enthusiastic door staff, where the concept has been twisted with the addition of the word ‘industry’, presenting hospitality as an instrumentally rather than ethically based phenomenon.

Sources:

Lawson, H. (1925; posted 2020) Poetical Works of Henry Lawson, Angus and Robertson * A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook * eBook No.: 2001251h.html. Accessed 5-04-2025 from https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks20/2001251h.html#CherryTreeInn

Sandiford, P.J. & Divers, P. (2011). ‘The public house and its role with society’s margins’ International Journal of Hospitality Management 30(4), 765-773. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.12.008

Sandiford, P.J. & Divers, P. (2014). ‘The public house as a 21st Century socially responsible community institution’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 41, 88-96. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.005

*****

Playing with music in business scholarship: February 2025

Peter John Sandiford, February 2025

I’ve been interested in different ways of thinking about, conducting and sharing social and business research for many years as is probably obvious given this website’s content. One area that I have used in my scholarship for a while has been music.

Lacking talent to write or perform music, I am more about listening. Every now and again something gels with me professionally rather than just for listening pleasure. An early discovery was Peter Honey’s collaboration with Pete Sweet and Dave Philips. I found a CD, Songs of Life and Learning (2000), in a UK charity shop and was intrigued. I was aware of Honey’s earlier work with Alan Mumford on learning styles (having taught learning theory and I even presented a conference paper on learning styles). Since then, I’ve often introduced the CD to students. Their reactions can be interesting and amusing; they often criticise the tunes and give little attention to the lyrics. To be honest the words are a little trite and forced, but it is clear that Peter Honey, who passed away earlier this month sought alternative ways of communicating his influential ideas – not surprising for someone who dedicated most of his career to understanding different approaches to learning..

Another influential (to me) musical experience stemmed from an MBA class on organisation and management, a few years ago. One of the course’s key themes was cognitive dissonance (a personal favourite). This concept helps personalise values and ethics and encourages us to reflect on responsibility and behaviour at work. The student was a musician who explained that dissonance is important in musical composition as well as psychologically (I also touched on emotional dissonance too) – indeed, Mozart’s String Quartet No19 in C major is often referred to as the Dissonance Quartet. This started me thinking about other examples. Soon after I started introducing students to the UK post-punk band Joy Division’s track Exercise One (1981, from London Records). I think this originated from one of the influential (John) Peel Sessions, for BBC radio). This track can be difficult and uncomfortable to listen to, and elicits bewilderment or even disgust from some, but I think this can be a powerful illustration of the discomfort (and value) that dissonance can contribute to. I tend to ask participants to reflect on their behaviour and feelings of dissonance, questioning how they experience and address unease when thinking about their behaviour; is it just about trying to reduce dissonant reactions to ‘bad’ behaviour, or is there also a need to become comfortable with discomfort? As a late ‘Boomer’ of the punk generation, we often celebrated the discord and dissonance that punk forced around us in music and society.

My third example here is another recent rediscovery of an old favourite. I was looking for a bit of musical content for a recent research day that I was asked to run. Showing my age, I revisited some more 1980’s post-punk; this time it was Chaz Jankel’s song Questionnaire. He had written for and played with Ian Dury and the Blockheads and this song offers a sort of blue-eyed funk to gently satirise the obsession with questionnaire surveys that so many researchers in our field continue to demonstrate.

Exercise One and Questionnaire are both available on youtube, but I can’t find any online material from Peter Honey’s CD, unfortunately. Does anyone else have any musical inspirations for business researchers and students? Please let us know your thoughts.

Leave a comment